The Department of Media, Culture, and Communication at New York University is pleased to announce the Neil Postman Graduate Student Conference, to be held on October 27-28, 2022. The conference will be a hybrid event, hosted in person in New York with some remote presentations. Our keynote speaker is Professor Wendy Hui Kyong Chun of Simon Fraser University.

Our theme this year is the Hinterlands of Media and Technology. What is peripheral and yet indispensable to media and technology production? What networks and relations may be obscured or revealed if we interrogate the constitution of the center? This year, we focus on the centrality of the ‘elsewhere’ and the ‘otherwise’ in the production of media experiences and media technologies. To consider the many historical, geographic, economic, and material dynamics at play, we center our inquiry around the notion of the hinterlands, and invite contributions to the question: What and where are the hinterlands of media and technology?

This conference would not be possible without the support of our co-sponsors: The Hagop Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies, the Integrated Design & Media Program at NYU Tandon School of Engineering, the Department of Performance Studies at NYU Tisch School of the Arts , the New York Center for Global Asia, and the Departments of Social and Cultural Analysis, Anthropology, and History at NYU College of Arts and Sciences.

SCHEDULE

Thursday October 27

3:00pm-3:10pm – Welcome

3:15pm-4:15pm – Interrogating Hinterlands through Creative Practice (In-person presenters; moderated by Marz Saffore)

Jamie Theophilos, Indiana University in Bloomington: Disrupting the Social Empire.

Today the negative impacts of social media are widely accepted, even if their scale and scope remain obscured. From the restructuring of the workforce and policing tactics to how we form interpersonal relationships, Big Tech has irrevocably changed our everyday lives in countless ways. The Social Empire is a forthcoming feature-length documentary about the implications of large social media platforms on all grassroots social movements fighting for a world worth living in. This film, which focuses explicitly on the effects of the company Meta and its affiliated platforms, is a collaboration with anarchist filmmakers from four countries, who all share similar concerns on the state of technology today. Through interviews, narration, archival footage, and motion graphics, this documentary showcases the voices of a myriad of activists, artists, scholars, and software engineers, all discussing key concepts and historical occurrences surrounding the practical manifestations of surveillance capitalism and its impact on marginalized communities. These voices include notable figures such as author Cory Doctorow, Tor Browser co-founder Allison Macrena, and groundbreaking digital rights organizations including Lucy Parsons Lab, Netizen, and the Civil Liberties Defense Center. While our documentary was designed with a broad audience in mind, we would be particularly excited for the opportunity to use the issues raised in our film as a catalyst for a deeper theoretical discussion with other critical media technology study thinkers. Our goal for this documentary and subsequent presentation is to showcase the vital need for grassroots movements to incorporate critical analysis and interrogation of their reliance on mainstream social media platforms into their daily praxis. By tracing the role played by Facebook and its affiliated platforms in the Tigrayan Genocide and the repression of participants in Standing Rock protests and the George Floyd uprising, we question just what kind of world Facebook has created and what might be required to stop it.

Film Website: https://thesocialempire.net/

Film Creators: https://sub.media/ (Canada and the US); https://antimidia.org/ (Brazil)

Part of the Media Collectives:

Hanna Dosenko, University of California, Irvine: “Soldier One Swipe Away.”

“Soldier One Swipe Away” is a screencast film based on the digital ethnographic research about online dating experiences of soldiers in a warzone in Ukraine. In 2020, amidst the Covid-19 pandemic, when this project emerged, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin said that there are no Russian soldiers in Ukraine. Using a dating app (Tinder), I attempted to prove that this is not the case: in fact, Russian forces have been present in Ukraine well before the most recent full-scale Russian invasion in February 2022. Swipe right, swipe left. They started to reveal themselves sooner than I thought. A man standing on a tank victoriously raising his AK-47s into the air somewhere in East Ukraine – not clear if he was Russian or a Ukrainian separatist. Swipe right, swipe left. “If Covid does not take you out, I will”, promised one of the soldiers’ descriptions. It took me less than 20 minutes to find what I was looking for – a man in uniform and a blue beret; I zoomed in on his stripe, and read: “Armed Forces of the Russian Federation” – he did not even hide it. I, on the other hand, never revealed my identity or the idea behind my project, as I go through dozens of matches per day, trying to make them speak to me. I filmed all of these interactions in real-time. Within the context of the ongoing war in Ukraine and the repeated acts of violence against the Ukrainian women, this project goes beyond witnessing the presence of the Russian soldiers. I will explore the digital platform Tinder as a mnemonic device that stores and remembers the profiles of potential dates, and simultaneously of people who commit war crimes on the territory of Ukraine – killing civilians, looting, but also raping. My responsibility as a woman, then, is to match with a soldier, with a clear intention to make him visible and accountable.

4:15pm-5:15pm – Open Poster Session with Refreshments

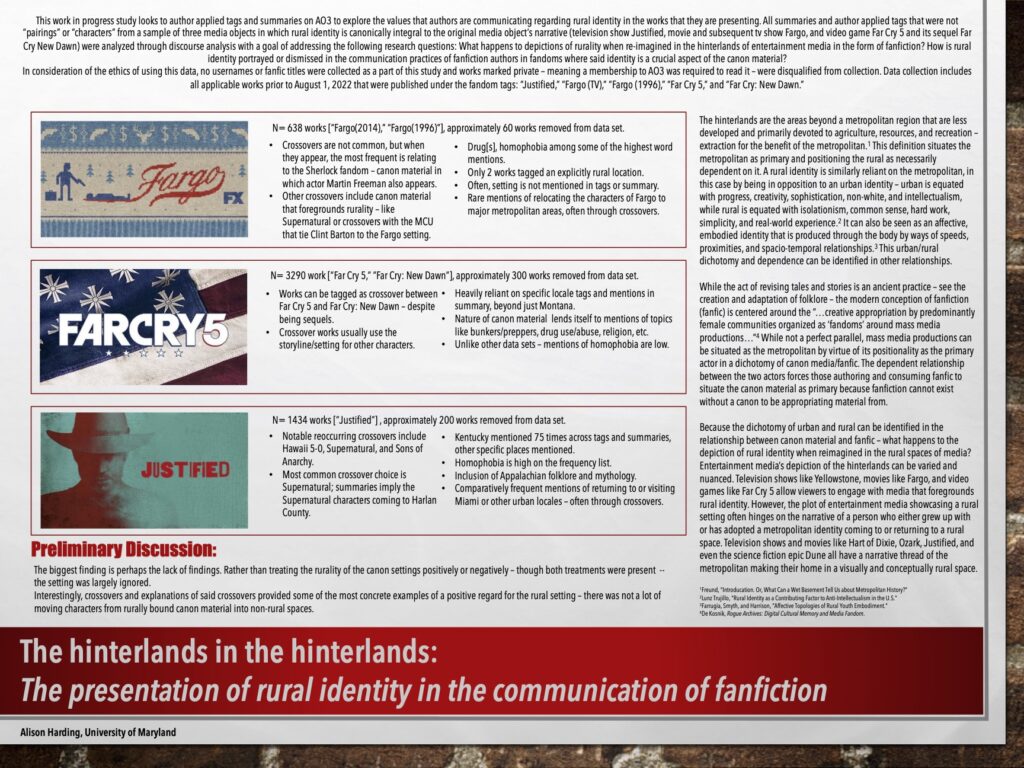

Alison Harding, University of Maryland: The hinterlands in the hinterlands: The presentation of rural identity in the communication of fanfiction.

Entertainment media’s depiction of the hinterlands can be varied and nuanced. Television shows like Yellowstone, movies like Fargo, and video games like Far Cry 5 allow viewers to engage with media that foregrounds rural identity. However, the plot of entertainment media showcasing a rural setting often hinges on the narrative of a person who either grew up with or has adopted a metropolitan identity coming to or returning to a rural space. Television shows and movies like Hart of Dixie, Ozark, Justified, and even the science fiction epic Dune all have a narrative thread of the metropolitan making their home in a visually and conceptually rural space. Once these pieces of entertainment media are released to the public, they become something more than just a piece of media. They take on emblematic qualities that allow fandom communities to form around them. In this environment, one can view fanfiction as the hinterlands of media entertainment. While fanfiction does not generally feed back into the canon material, it does allow for the generation of creative work and bolster fan community identity, while still being removed from the center of the narrative. Taking this one step further, what happens to these depictions of rurality when re-imagined in the hinterlands of entertainment media in the form of fanfiction? This study is a work in progress content analysis of the author generated tags on the volunteer run fanfiction archive, Archive of Our Own (AO3), in 3 fandoms where rural identity is a critical component of the canon media’s content. The study is exploratory in nature, taking a lens of embodied information practices to look at the question: How is rural identity portrayed or dismissed in the communication practices of fanfiction authors in fandoms where said identity is a crucial aspect of the canon material? Three fandoms will be analyzed: the television series Justified, the video game Far Cry 5, and the movie and related television series Fargo. Preliminary emergent findings will be presented in the form of a work in progress poster.

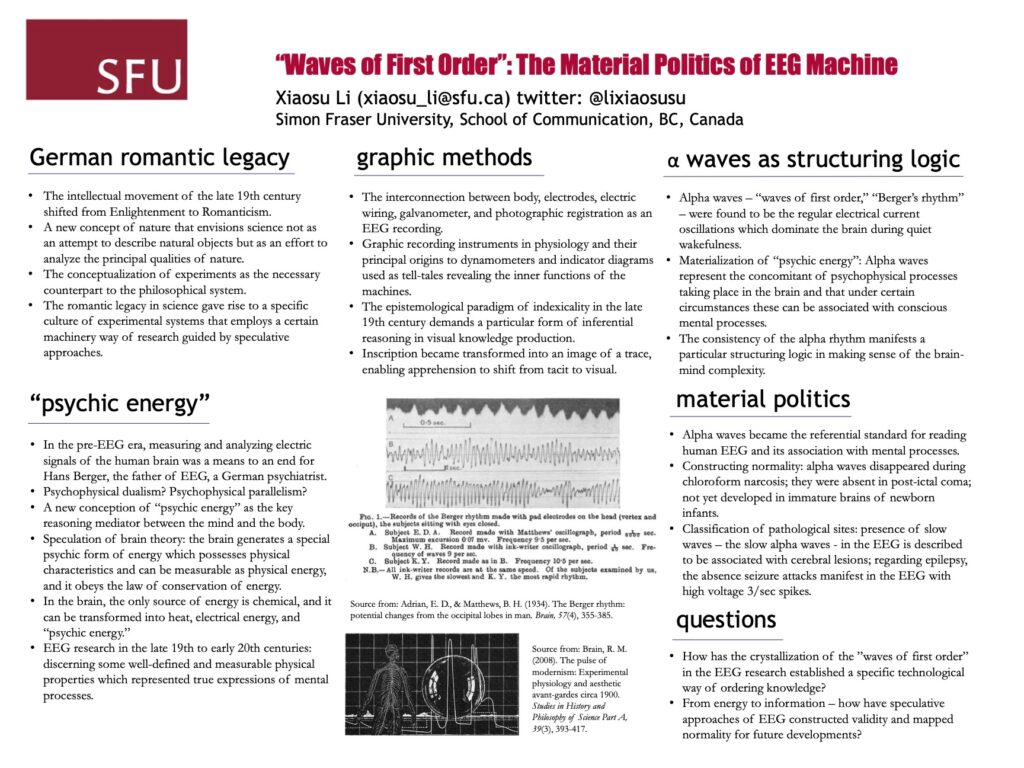

Xiaosu Li, Simon Fraser University, School of Communication: “Waves of First Order”: The Material Politics of EEG Machine.

Electricity seemed a ghostly and elusive phenomenon to many thinkers and scientists in the 19 – 20 centuries. Ever since the time of Luigi Galvani with his discovery of animal electricity, many researchers had become curious about the connection between electricity and human consciousness. With a broader philosophical shift in science from enlightenment to romanticism in the 19th century, scientists became to seek unity in human and nature. The culture of experimental systems and the emergence of graphic methods encouraged scientific ways to materialize human psychic states. With years of dedication of exploring the forces of electricity, magnetism, and galvanism and their utilization in experimenting with brain imaging, German psychiatrist Hans Berger found “waves of first order” in the human brain and established the standard of Electroencephalography (EEG) in the early 20th century. Berger’s first report on the EEG revealed the basic brain rhythm: the alpha waves. Since its establishment in historical brain imaging, the alpha waves remained the cardinal pivotal point of interpretating the EEG and differentiating brainwaves from artifacts and noises. This study looks at archives, academic literature, and descriptions of the historical development of the EEG machine to examine the entanglements of machines and rhythmic representations in structuring speculative knowledge of mental states.

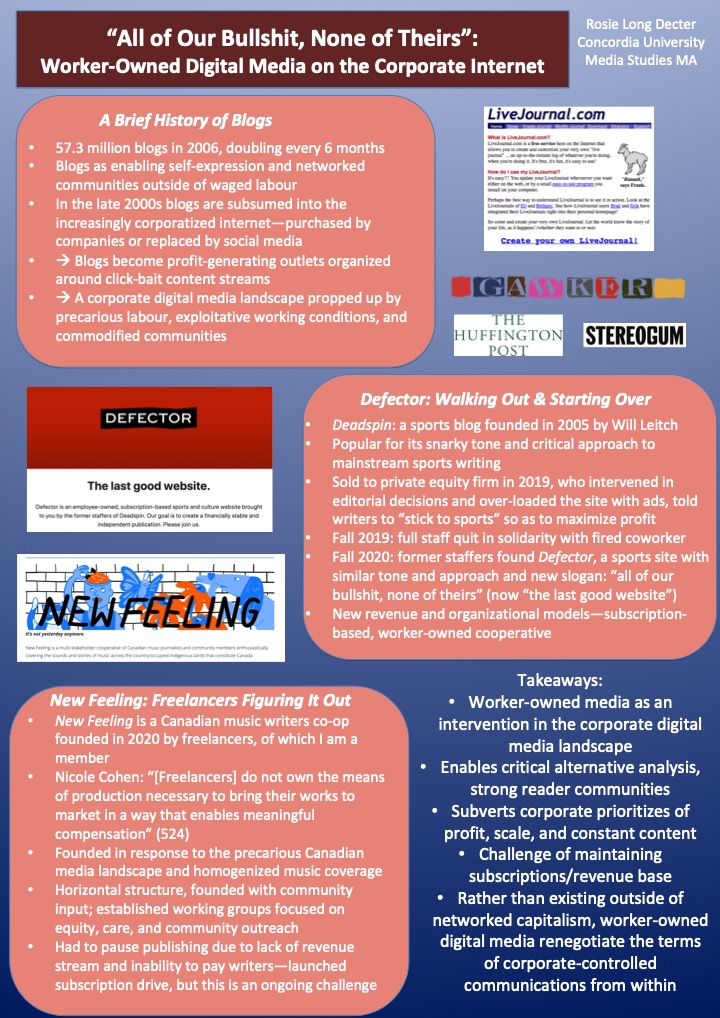

Rosie Long Decter, Concordia University: “All of Our Bullshit, None of Theirs”: Worker-Owned Digital Media on the Corporate Internet.

In the beginning, there were blogs. The early stages of the Internet abounded with networked blogging communities, where individual Internet users gathered online to discuss and debate their shared interests. With the corporatization of the Internet in the late 2000s and 2010s, blogging became increasingly commodified: large companies and private equity firms bought popular sites, while major platforms became the go-to spaces for individual posting. Corporations subsumed the independent media creation of the Internet. As Linda Jean Kenix writes in her book Alternative and Mainstream Media: The Converging Spectrum, “one has to wonder if the only avenue for an online public sphere in the modern, corporatized, digital era is squarely within a corporate economic context” (103). This paper looks at the ways in which particular digital media sites are pushing back against their own subsumption. I highlight the popular sports website Defector, streaming service Means TV, and music coop New Feeling (of which I am a member). All three are cooperatively owned media outlets founded in response to the precarious working conditions and loss of journalistic autonomy which dominate the new media landscape. Defector specifically was founded out of the ashes of Deadspin, a popular blog run into the ground by corporate takeovers—hence their slogan, “all of our bullshit, none of theirs.” I argue that, in taking control of their working conditions, these sites demonstrate possible alternative modes of operating on the corporatized Internet. Using Nicole S. Cohen’s Marxist analysis of digital media precarity and Elise Thorburn’s work on the subsumption of communications technologies, I identify the historical context in which Defector, Means TV, and New Feeling emerge as different ways of doing digital media, neither entirely mainstream or alternative. Each publication is still mired in the online networks of corporate platforms like Twitter and Facebook andcompetes for subscriber support in an attention economy. However, they also de-prioritize competition itself, refusing an easy reproduction of the logics of corporate media. In this sense, they do not exist outside the “corporate economic context,” but are renegotiating the conditions of communication within it. Works Cited Cohen, Nicole S. “Cultural Work as a Site of Struggle: Freelancers and Exploitation.” tripleC, vol. 10, no. 2, 2012, pp. 141-155. TripleC, doi: 10.31269/triplec.v10i2.384. —–. “Entrepreneurial Journalism and the Precarious State of Media Work.” South Atlantic Quarterly, vol. 114, no. 3, 2015, pp. 513-533. Duke University Press, doi: 10.1215/00382876-3130723. —–. “From Pink Slips to Pink Slime: Transforming Media Labour in a Digital Age.” The Communication Review, vol. 18, no. 2, 2015, pp. 98-122. Taylor & Francis, doi: 10.1080/10714421.2015.1031996. Kenix, Linda Jean. Alternative and Mainstream Media: The Converging Spectrum. Bloomsbury Academic, 2012. Thorburn, Elise D. “Networked Social Reproduction: Crises in the Integrated Circuit.” TripleC, vol. 14, no. 2, 2016, pp. 380-396.

Sui Wang, University of Southern California: Sounds of Belonging: Sonic Diaspora in Overseas Chinese Radio Stations.

The multiplication of media forms including music, TV shows, radio programs, and streaming videos accelerates the mediatization of social life. Alongside the flow of capital and people, technological connectivity facilitates the formation of “global diasporic Chinese media sphere,” which arguably contributes to transnational imagination of China and transformation of diasporic identities of overseas Chinese. Albeit dispersed and anchorless, the diasporic public spheres are, in Appadurai’s words, “no longer small, marginal, or exceptional. They are part of the cultural dynamic of urban life in most countries and continents, in which migration and mass mediation constitute a new sense of the global as modern and the modern as global” (10). However, viewed from a global media landscape, Chinese media occupies a rather marginal space, and thus, is easily dismissed as “ethnic media.” Struggling to claim a presence in global media space, Chinese/Sinophone communities worldwide confront the plight by continually speaking out in the niche media sphere of their own. This paper attempts an analysis of sonic Chinese diaspora with specific focus on overseas Chinese radio stations: how does listening to Chinese radio make diasporic identifications of immigrant communities? By locating radio in a larger context of diasporic media, we can paint a mosaic picture of overseas Chinese imagination. The access to media resources, not only transforms migration experience, but also later processes of relocation, social inclusion, participation, and gaining visibility in the residing country. The diasporic media provides a virtual space in which borders, identities, and belongings are constructed, negotiated, and re-imagined. Rethinking diaspora in a digital context allows us to examine how traditional parameters like “displacement” and “mobility” are mapped onto contemporary geopolitical dynamics. The travel of voices that are afforded by radio waves create a temporal, virtual, home-coming for overseas Chinese. Drawing on interviews with radio producers and transcriptions of Chinese radio programs, this paper adopts a mixed method of textual analysis and sonic ethnography in a bid to parse out intricacies of diasporic identity negotiation via self-narratives of Chinese immigrants.

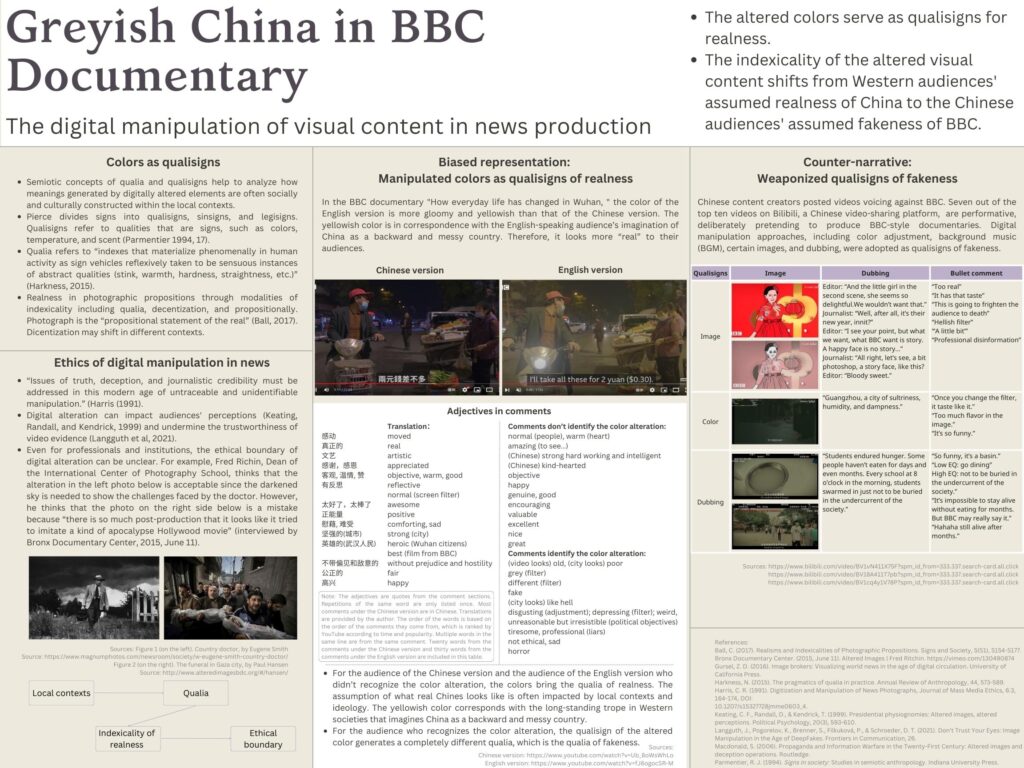

Zhuoru Deng, New York University: Greyish China in BBC documentary: The digital manipulation of visual content in news production.

With technological developments, photography and video have served as indispensable parts of storytelling. The increasingly visualized international journalism raises concerns about the fairness of local communities’ representation. The inequalities of international journalism affect global communication, with western mainstream media having more access, resources, and audiences for their international stories. Visual contents, including images and videos, are subjected to digital manipulation that may contribute to the discrimination of the global South and minorities. As media anthropologist Zeynep Devrim Gürsel (2016) has argued, “news images are ‘formative fictions,’ constructed representations that reflect current events yet simultaneously shape ways of imagining the world and political possibilities within it. As formative fictions, news images have consequences and play a role in world making”(11). Therefore, though news images and videos are often assumed to be objective by the mass audience, they are susceptible to the media frames. In this paper, I will focus on the case of a BBC documentary about Wuhan in the Covid 19 pandemic. In December 2020, BBC News posted a documentary on YouTube, including an English version named “How everyday life has changed in Wuhan” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fJ6ogocSR-M) and a Chinese version called “一年後,新冠 疫情如何改變了武漢” (Translation by the author: A year later, how the pandemic has changed Wuhan) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ub_8oWsWhLo). The contents of the two versions are almost identical. Still, the color of the English version is more gloomy and yellowish than that of the Chinese version, which corresponds to the long-standing trope that imagines China as a backward and messy country. Infuriated by the misrepresentation, Chinese content creators have deliberately used video editing technologies to produce hundreds of videos that criticize and even mock the BBC. This paper is aimed to discuss how narratives are constructed and circulated by the digital manipulation of visual content in news materials. More specifically, it discusses how video editing technologies contribute to both the world-making imaginations of western international media and the counter-narratives of local communities.

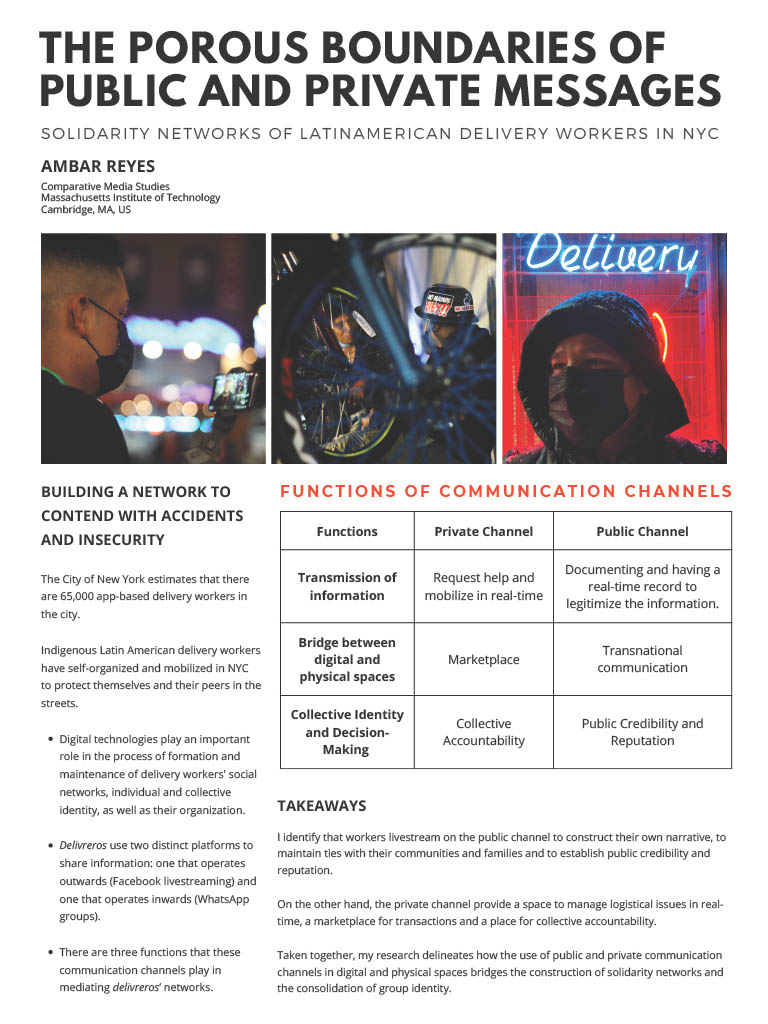

Ambar Reyes, MIT: The porous boundaries of public and private messages: solidarity networks of Latinamerican delivery workers in NYC’s platform economy.

My proposed paper examines how indigenous Latin American migrant delivery workers in NYC exercise agency, build community and resist platform control through their use of digital social networks and communication technologies. Scholars such as Gray (2019) and Rosenblat (2017) have shown how the gig economy ecosystem is underpinned by long-standing tensions between companies and workers; I argue that migrant delivery workers defy information and knowledge asymmetries by repurposing the technology that has been built as a means for control. Marginalized, misrepresented, or ignored by mainstream media and governmental actors, information and communication technologies allow migrant delivery workers to bypass traditional channels, disseminate their own stories, and create community. Building on ethnographic fieldwork in NYC, I map how delivery workers, located at the social and geographic periphery, communicate and engage collectively through digital platforms. My research reveals two digital platforms that workers use to share information: one that operates inwards (Whatsapp) and another that operates outwards (Facebook). These two forms of communication represent opposite sides of the spectrum between public and private communication, and ephemeral and permanent information. Delivery workers use Facebook to live-stream accidents, upload information about bike robberies, and document their actions. I identify three objectives to live-stream: it helps workers construct their own narrative, it maintains transnational ties and it establishes public credibility and reputation. They use WhatsApp to coordinate, request help, and mobilize in real-time. I analyze how public and private means of communication facilitate and constrain social forms of organization. These layers of communication synergize to form a transnational distributed knowledge network and to shape and interpret the collective identity of migrant delivery workers. In sum, my essay—which is drawn from the Master’s thesis I am currently completing at MIT—illuminates how the flow of information through different spaces and times enables migrant workers to construct a place for subversion and negotiation with roles assigned to them by broader socio-political forces. Thus, I argue that Latin American delivery workers’ use of technology provides a unique glimpse into the convergence of social networks, media culture, and social movements within the context of contemporary gig labor and migrant organization.

5:15pm-6:30pm – The Edge of Experience (Online presenters; moderated by Anna Stielau)

NEO Yee Win, National University of Singapore: Too Hot, Too Smelly?: Experiencing Heat and Odour in E-Waste Recycling.

With the problem of electronic waste gaining attention, e-waste recycling avenues have proliferated across Singapore, making it extremely easy for individuals and organisations alike to dispose or pass on their used devices. Virtual tours on YouTube also make the process of recycling e-waste more accessible, transparent, and accountable. However, the one thing visual and audio mediums cannot reproduce is materiality, and I argue that exploring e- waste recycling through thermal and odour perceptions help humans better live with technology. I first take heat as an entry point to understand the e-waste recycling process in Singapore, where the tropical weather is a regular enemy of labourers and heat-emitting media technologies, but which does not deter the mass consumption of new and newer devices, and thus more and more e-waste. How does heat affect the e-waste recycling process, and how do the thermal experiences of e-waste handlers shape their understandings of sustainable futures? From virtual tours, the e-waste recycling process is shown to encompass both ends of the heat spectrum. Air conditioning is a mainstay of the recycling process, being present in shopping centres, where e-waste bins are typically located, and recycling centres, where e- waste is transported to. At the same time, e-waste recycling is a laborious process, and labour makes people sweat. The artificiality of cooled environments, even for green purposes, also generates waste heat, thereby contributing to greenhouse emissions and climate change. With heat comes another aspect of materiality: smell. Heat evokes sweat, germs, and thus odour. By incorporating coolness into the chain of e-waste recycling, how is the smell of e- waste further mediated? How does smell shape perceptions of waste jobs like e-waste recyclers? However significant and essential people may think of waste management jobs, the industry continues to face manpower crunches as it is thought of as dirty, dangerous, and demeaning. Can adjusting the heat and smell of e-waste recycling jobs enhance their palatability to the working population? It is through these questions that I hope to sketch accessible, entry points into sustainable media practices.

Kendra Lee Sanders, University of Chicago: Milky Media: The Technological and Symbolic Rendering of Cows in Cinema and After

Andrea Arnold’s documentary Cow (United Kingdom, 2021) may seem trite. The film chronicles the life of dairy cow Luma until her death, a birth-to-slaughter narrative structure that has been commonly employed in written texts, such as Michael Pollan’s 2002 essay “Power Steer.” A closer look, however, reveals something more interesting going on between Luma’s story and the cinematic medium used to capture it, that is, a connection between Luma’s life and the material substrate of cinema as traditionally manufactured using cow remains. While Cow may be shot digitally, the film participates in a long history of technologically and symbolically rendering animals. In this essay, I argue that animals, and in particular cows, have and continue to be the indispensable raw material of visual technologies. Following Nicole Shukin, who astutely connects the development of moving pictures to the slaughterhouses of Chicago and Cincinnati, I examine how moving image technologies are turned back onto animals with the adoption of digital wearables in the agriculture industry.1 I trace this yet-to-be-made genealogy from the protocinematic spectacle of slaughterhouse tours and George Eastman’s development of photographic gelatin emulsion and subsequent modification of cow bodies for more sensitive film stocks to wearable cameras and sensors attached to dairy cattle in order to optimize milk production. These wearable technologies engage animals in a renewed logic of disassembly, a logic of digital fragmentation in which their biological functions are made discrete and rendered as charts and graphs on farmer-friendly mobile applications. Agriculture catalyzed human civilization, and domesticated cattle were of two-fold dietary importance. Their complex digestive systems converted energy for humans and provided byproducts advantageous for survival, like milk. Displaced outside city centers, these farms have traditionally been conceived as the hinterland of the metropole. Now, admits the digital era, I contend this dairy hinterland is also the hinterland of the ubiquitous and supposed ‘immateriality’ of digital media and culture. The animal robotics market is booming; with dairy farms as one of the biggest adopters. This new sector brings together two of the biggest world industries: agriculture and information technology. The union between the two enterprises seizes a powerful seat that reproduces forms of power and reshapes relationships between humans and animals.

Merve Ünsal, UC Santa Cruz: Artistic Practice in Media as Hinterlands of Post-Surveillance: Tuning into Mardin.

Catastrophes discontinue history, bury information and knowledge(s)—or so we are told. I disagree with this view of catastrophes as acts of burial. In my research, my goal is not to unearth this knowledge and information. Rather I want to expose the structures that have compelled the information and knowledge to be invisible, unseeable, and unavailable, which requires we think beyond reckoning: Practice needs to stay with the questions, because it is precisely the inability to articulate aloud the questions around catastrophe that require making work. This formidable task requires that, instead of engaging with established methods of looking, we invent structures that allow us to be entangled with catastrophes, places, and bodies alike. We need new paradigms of making that can restore the catastrophe as a transformative state and not as a rupturing event. For the charged context of a contemporary art biennial in Mardin (located in the southeast of Turkey, a site of conflict between the state of Turkey and the Kurds), I produced two works. Into the Wind is a layered audio recording composed of field recordings from a device held between two bodies, found radio/television narratives of resistance movements, notes from a digital theremin tracing drone footage of situations when the wrong person was killed, a whispered response in the form of a fairy tale that I composed, and wind recordings from multiple locations. The work actively imagines a kinship through listening/eavesdropping—a way of being together, remembering together, feeling together. This work is installed in a public space. The second work, A few words to drones is a sentence addressed to the imagined and real drones that surveil, “Both metal and plastic have been fatigued.” This sentence installed on a large-scale in the public space, is meant to function as a warning, an observation, and a fact, presenting two sides: serving the function of providing shade for those looking up and speaking to those looking down. How do we consolidate and transform these tools of surveillance to expose the structures that have made information and knowledge unavailable through artistic practice? How does artistic practice help envision the post-surveillance?

Friday October 28

8:00am – 9:00am – Breakfast

9:00am – 9:15am – Welcome

9:15am – 10:35am – Internal Hinterlands (In-person presenters, moderated by Amy Zhang)

Wan-Chun Huang, East Asian Studies, NYU: Animating Boys-love on Chinese Television.

This paper discusses how the emergence of Chinese TV animations on the theme of boys- love since the 2020s, on the one hand, under the watchful eyes of the Chinese censorship regarding homosexuality but, on the other hand, shows awareness of censorship and skirts it to attract audiences. To that end, I use three cases of television animations—Thousand Autumn (2021), Heaven Official’s Blessing (2021), and Legend of Exorcism (2020)—all of which share a boys-love romance in an immortal setting to understand the intrinsic relationship between Chinese TV animation’s censorship, creators, characters, and audiences. In this paper, I focus on how animations help get the taboo messages past censors through lack of realism (animated background, unrealistic drawings of humans, and fantasy otherworldly settings). In addition, these animations often employ ambiguity such as the blushing of a character when teased which can be interpreted as embarrassment or romantic affection which also gets it past the censors. When audience members watch the animations, the lack of realism causes them to take a step back from the program and regain their awareness, namely, the distancing effect (Brecht 1964). They are then free to re-engage with their own desired fantasy to interpret the ambiguity as what it really is—the banned theme of boys-love. Moreover, I join the discussion of “the mode of animation” (Silvio 2019) to expand the understanding the television animation in contemporary China not as mere entertainment but as a way to rethink the boundaries of diverse mediums where the theme of boys-love animations was derived from (that is, novels, radio programming, and manga). This new theme reimagines the relationships between multiple media modalities that evade censorship. In doing so, I discuss the possibilities for a Chinese mode of animation in which censorship is considered as part of the production process where animations avoided the censorship that banned the other mediums which they were based upon. This paper will approach Chinese animation’s televisual space as where animation producers and audiences were empowered to bend a government-sanctioned producing and viewing experiences.

Sandeep Mertia, NYU MCC: Remote Futures: Fieldnotes on Non-Metropolitan Spaces of “Post-COVID” Digital Acceleration

Drawing on nearly two years of in-person and virtual ethnographic fieldwork and archival research, my dissertation explores the rise of techno-entrepreneurship and the governance of aspiration in India. The federal government’s flagship ‘Startup India’ program, launched in 2016, now has 68,000+ registered start-ups, many also supported by allied initiatives of state governments across small cities. Focusing on the intertwining of digital infrastructures, state policies for start-up incubation, and the aspirational subjectivities of entrepreneurs in different urban contexts, my project shifts attention away from global technology hubs such as Bangalore to smaller cities such as Jodhpur and Jaipur. In doing so, I examine how processes of a) digital mediation, scale, mobility, connectivity, “planetary-scale computing” (Bratton 2015), and b) the cultural horizon of futurity take on qualitatively different spatial forms in small cities than in idealized metropolitan imaginaries of future- and place-making. In this paper, I examine how entrepreneurs have pivoted the ongoing crisis into a mega opportunity for “post-COVID” digital future making in tier-2 and -3 cities in India. Indian start- ups have raised more capital in 2020 and 2021 than ever before. I describe how my interlocutors, who claim that “covid has been a big boom,” spatialize global digital acceleration in context. Exploring the shifting logics of presence, remote work, and scale, I offer an ethnographic analysis of anticipatory practices of digital future making in / from small cities in India. I also describe how the state instituted new app challenges, hackathons, and grants for entrepreneurs to solve pandemic related problems; and how the state publicized start-ups that won these competitions. In parsing these, I analyze how the disruption-philic ethos of techno-entrepreneurship, both at the level of the state and start-ups, steers the spatial modulation of aspiration and speculative value with/in digital media as millions languish in the same present.

Sasha Crawford-Holland, University of Chicago: Oppressive Heat: Weather Coverage and the Vicissitudes of the Local.

During the 1995 heat wave that killed 739 Chicagoans, local television mediated the heat as a fun meteorological anomaly. For days, government and media institutions failed to register the event as a disaster. Only when the heat subsided and the county morgue became inundated with corpses did newsrooms belatedly initiate their protocols of catastrophe coverage. The scene localized this diffuse disaster to a central ground zero but obscured the stratifications that had distributed heat differentially to the point of death. While climate activists often rightly emphasize the importance of attending to local contexts, the heat wave illustrates that tensions between global generalization and local precision, between center and periphery, persist recursively at any scale. Local news is fraught with conflicts such as competing priorities urban, suburban, and rural audiences. In this presentation, I examine how local TV coverage negotiated these conflicts during the 1995 Chicago heat wave, arguing that the aesthetics of temperature are intricately entangled in the politics of population. Local weathercasts generalize local environments and aggregate risk perception despite audiences’ diverse circumstances, producing theories of the local based on demographic priorities. Geographical centers can become demographically peripheral and the seeming hinterlands can become ideological centers under the infrastructural demands of market populism that prioritize white, middle-class viewers. Temperature provides a compelling lens onto this problem because, as an average, its measurement always involves political decisions about who and what to count and discount; forecasts establish scalar frames that foreground certain relations over others. For example, meteorologists predict heat’s “oppressiveness” based on soil moisture and atmospheric humidity, whereas activists identify disinvestment and housing discrimination as causes of “oppressive” heat. Taking methodological inspiration from temperature’s contingency, I investigate how local news and weather coverage of the heat wave constructed the local through protocols of averaging that eclipsed the needs of vulnerable populations. How does local television scale thermal perception? How do broadcast media prioritize certain communities over others? And what does it mean to call something “local” in the first place? Often overlooked by humanities scholars, local television is a theoretical hinterland that holds rich histories of power and place.

10:35am – 10:45am – Break

10:45am – 12:20pm – Sensing Mediation (In-person presenters; moderated by Mara Mills)

Tinghao Zhou, University of California, Santa Barbara: The Smell of Globalization

Planned obsolescence of the consumer electronics and technologies industry designs the material lifecycle of data, paving the way for a profit-pursuing, yet insufficiently-regulated journey, conceived as the “global industrial metabolism” of e-waste. However, the material afterlife of user media, I argue, should be more than a story of what would happen when personal digital devices and electronic machines reach the end of their designed life cycles. It should also be about human lives after the relocation, redistribution, and recycling of these “dead” electronic materials, about how life itself is being restructured, reorganized, and reconstituted. Material “residuals” of digital media and information technologies, when being dismantled, burnt, and degraded into simpler metallic elements and chemical forms that will in turn over-saturate and destructively transform the local ecology, also take critical parts in the body’s metabolism of workers and towners who live in the underdeveloped recycling center. Guiyu, once the largest e-waste recycling town of the world, was characterized by a pungent, penetrating smell of chemicals and plastics burning, commonly referred to as the Guiyu Wei (the smell of Guiyu) by both the locals and officials. Shrouded in a kind of “environmental terror” fabricated by the network of unidentified toxins and chemicals, breathing had become a precarious bodily (re)action that constantly put people’s lives at risk. Recent provincial environmental projects, with the goal of controlling Guiyu’s e-waste pollution, had not only invested in the planning and building of the “dead media infrastructure” but also proposed to reconfigure the medium of perception (atmosphere, water, chemicals, etc.) in which olfactory experience takes place. Taking Guiyu as its central case, this essay tries to present a prolonged material afterlife of digital media in the era of globalization, which is intimately intertwined with the life and livelihood of the local workforce and community, and to theorize olfactory mediation as a salient concern for environmental media studies. The volatile quality of odorants breeds the unstable ontology of smell and also provokes some of the central questions to this paper: How does globalization smell like? How can we index the smell of globalization? Can we actually index smell? What is the affective relationship between these indices and the indigenous community? Is smell fundamentally “anti-indexical”?

Angus Tarnawsky, Concordia: Sound, Sound(s), Sound(ings): Listening to the Lachine Canal

The Lachine Canal is located in the southwest portion of Tiohtià:ke (Montréal) and was the first canal in so-called Canada. The land where it is located was once a frequent meeting place for many different Indigenous peoples, including the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) and Anishinaabe. Reconfigured over time by fourteen-and-a-half kilometres of industrial canal infrastructure, it is now filled with residential condo buildings and interconnected urban green spaces. It should not be forgotten that both the canal itself, along with newer developments, are built on stolen Indigenous land. While the visual realities of this takeover are immediately apparent through the alteration of the spatial landscape, settler modifications have also shaped the sonic environment. These changes might be perceptible in audible or sonic forms, but sometimes, the changes are not explicitly apparent. Further, it should be understood that the various kinds of phenomena sensed by one person cannot always be easily sensed by another, and that such information is rarely accessible to everyone, or even at all times. Taking these points into consideration, I follow the lead of Stó:lō scholar Dylan Robinson, and Canadian sound studies researcher Andra McCartney to ask: How can the sonic environment of the Lachine Canal be experienced in ways that attend to settler colonialism? And in turn, what kinds of experiences can materially change the sonic environment of the canal in the present? I start by focusing on practices of soundwalking to find out who and what can be heard on the Lachine Canal. This is followed with an analysis of what facets of the sonic environment everyday listeners might instinctively notice, and then attune themselves towards. And last, I investigate how clarifications of perspective and individual positionality might serve to change what is heard, as well as to understand what sounds, voices, and histories should be prioritized, and amplified in everyday shared spaces along the canal.

Meesh Fradkin, McGill University: Plus noise unlock

Do text-to-voice technologies such as screen readers create digital acoustic shadows when they are incompatible with particular software? Having one’s access needs denied is a particular way of knowing. But, what takes place when this is combined with sound as a way of knowing? Is the technology—or the people behind the technology—concerned with the barriers it creates? These questions come from my personal screen reader struggles with software such as Max/MSP. By using the Walkthrough method (Light et al. 2018; Morris & Murray 2018) with Max/MSP, this paper pays special attention to the relationship that screen readers have with digital acoustic shadows (Eidsheim 2021) and acoustemology (Feld 1984; Feld 1996; Feld 2004; Feld 2015) when digital tools become further inaccessible to people who have already been rendered invisible by a software or algorithm. Working in the Max/MSP environment is inaccessible for me. I am currently building a patch in Max/MSP that incorporates a number of zsa objects to detect for sounds that have a wide and flat spectrum, fed in through a pretty standard gaming headset. When I unlock the patch while making use of my screen reader, I am met with “plus noise unlock.” If I want to have the documentation tell me how Cycling 74, the development company behind Max, defines zsa.bark~ in their software, my screen reader tells me the title of the reference, rather than the actual description. In other words, I can’t rely on my screen reader when working on a patch. Although Max is often thought of as being as limitless as can be when it comes to technology, it lacks compatibility with many standard iOS accessibility features. Outside of these issues, Max is also the best tool for building the kind of digital music instrument that I am working on. This paper considers some of the barriers that are posed by Max/MSP. In doing so, I call for bringing more recognition to inaccessibility (from a disability studies perspective) throughout the sonic dimensions of machine learning technologies.

Laura Boyce, McGill University: “If you’re hearing, this please listen” : Voices of Mourning through the Wind Phone (Kaze No Denwa)

How might we speak to the missing and the dead? The wind phone, a white telephone booth with a disconnected rotary phone inside, provides a means of doing so. The phone sits overlooking the ocean in the Bell Gardia Kujira-Yama garden, near the town of Ōtsuchi, Japan–a site devastated by the 2011 Tohoku tsunami. Its creator, Itaru Sasaki, named it kaze no denwa, the wind phone, for its purpose is to let the wind ‘carry’ the voices of the living to their missing and deceased loved ones. Providing a location, medium, and ritual through which voice is substituted for physical remains, the wind phone uniquely responds to the difficulty of mourning in the wake of natural disaster. As a technology of mourning, the wind phone provides a space where visitors can reconcile their altered relation to the dead. What takes place is a renegotiation of mourning, where rhetorical devices, like apostrophe and prosopopoeia, along with nostalgic media—the rotary telephone—summon the dead and give them voice, all in the psychically and spiritually dense confines of a phone booth. Taking on multiple forms, the wind phone offers an interactive experience which is not necessarily available through traditional material objects and rituals associated with mourning. It differs in that its purpose is to provide a place and an apparatus for people to transmit messages to the dead as well as to listen for and sense their reciprocal, (absent) presence. Through its site-specific attributes, the wind phone allows visitors to confront (and sometimes disavow) the absence of the dead through the nostalgic performance of a rotary telephone call.

12:20pm – 1:30pm – Lunch

1:30pm – 3:05pm – Media, Infrastructure, and Empire (In-person presenters; moderated by Helga Tawil-Souri)

Stephen N. Borunda, UC Santa Barbara: Media Laboratories: Trinity and the Politics of Nonlife in the Chihuahuan Desert

Contrary to popular discourse, the world’s first atomic “test” (codenamed Trinity) in the Chihuahuan Desert in southern New Mexico did not occur in an isolated, remote, or barren place. Rather, the “test” carried out on July 16, 1945, occurred in a desert, borderland region with a lengthy history of colonialism, the largest percentage of Latinx populations, and the second-largest percentage of Indigenous peoples amongst US states. Thus, it is surprising that the early history of atomic media and atomic infrastructures in New Mexico remain mostly unexamined through the lens of coloniality (Quijano 2000). Coloniality is a framework of analysis that considers the reverberations of colonialism after its formal conclusion; coloniality also underscores how modernity requires particular spaces to become its “testing-grounds” (Quijano, Wallerstein 1992). In this presentation, I argue that coloniality and its requisite experimental sites lead us to consider the history of Trinity through the concept of the media laboratory. Drawing on Natalie Koch’s scholarship on desert laboratories (2020), I contend that media laboratories, like the Chihuahuan Desert, are sites that have and continue to operate at the intersection of media technologies of representation and extraction. During the atomic blast from Trinity, scientists used film strips as environmental sensors in their attempts to understand the radiation emitted from the clandestine blast. Alternatively, in the present, local survivors or their families in the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium have used intermedial approaches to activist media—from online archives to YouTube to a developing documentary to their own bodies—to sense and represent the impacts of the slow violence of the radiation from Trinity. These deployments of film and media convey that the media laboratory is always a contested terrain. This concept then entangles I) aesthetic technologies like film strips and activist documentaries, and II) material practices of extraction. Through a constant feedback loop between aesthetic practices and the toxic materiality of the nuclear industry, this desert region, and its inhabitants are relegated to the realm of the nonliving and the sacrificial (Povinelli 2017). In other words, the desert as a media laboratory names and materializes the necropolitics that undergird modernity’s energy and media infrastructures.

Alexander Jenseth, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute: There Are No Hinterlands: The Warped Geography of Media Infrastructure

The Hinterlands/Metropole or Hinterlands/City dichotomy is one teaming with potential for theoretical and critical inquiry. Drawing attention to the “beyond” and “unseen” are indeed vital activities for scholarship in and around Media Studies. This paper, utilizing the work of scholars deeply relevant to this question (Brechin, 1999; Brenner, 2014; Bridge, 2015; Bratton, 2015), posits that perhaps the hinterlands/metropole dichotomy in itself can lead to obfuscation; or at the least, given the planetary-scale nature of so many large overlapping infrastructural systems (Brenner, 2014; Bratton, 2015; Arboleda, 2020), worthy of critical (re)consideration. Drawing on work from my early dissertation research, this paper will demonstrate why media technologies may be usefully considered as forming a networked “megastructure” (Bratton, 2015), with the “hinterlands” a crucial part therein. If infrastructures of varying type are the means by which the materials (ex. minerals) from “elsewhere” become the built-environs (ex. data centers) of our “here,” then collapsing that difference may itself provide a twist on the initial distinction; this also further elaborates on the important notion of—“here” and “there” being so deeply intertwined within planetary infrastructural systems—zones typically written as “extraction zones” or “out there” are in fact right here. Our media technologies are the built environment—what Gray Brechin (1999) called “inverted minescapes”—of the “hinterlands” from whence their materials (minerals) were drawn. Troubling the initial distinction, I will demonstrate how allowing the extraction and violence of “out there” to in fact be considered part and parcel of the objects and systems we so rely on “here,” offers a slightly different lens for asking after the questions on offer for this conference. In many ways distance and inside/outside distinctions have been warped through the logic of the many planetary infrastructural systems that our media technologies rely so heavily one—and that in turn rely on those same technologies. What happens when you bring the hinterlands into the metropole, troubling that depth and distance, to make clear that these seemingly disparate zones, intertwined via infrastructures-of-infrastructures (megastructures), ought be thought of as one and the same.

Nicolas Rueda, University of Chicago: Demon Plane Energetics: DOOM (1993) and the Resource Frontiers of Early FPS Space

Key early PC first-person shooters of the 1990s fixate on sites of energy production: an endless procession of polygonal hinterlands dominated by power plants and dams, threaded together by bunkerlike spaces and research facilities. Game designers of this era framed the newly navigable, dimensional spaces of PC gaming as a vast resource frontier, a set of distant lands where fictional battles over infrastructure echo efforts to harness player attention. These game spaces resonate with the industrial conditions that made them possible, offering a formal elaboration of postwar American energetics born of a fortuitous match between the limitations of game engines and a subcultural imaginary drawn to infrastructural aesthetics, demonology, and techno-pessimism. Drawing variously on Georges Bataille’s theory of expenditure, Paul Virilio’s bunker archeology, and McKenzie Wark’s theorization of gamespace, this paper offers a close reading of maps from 1993’s DOOM alongside an account of iD Software’s evolving elaboration of a serialized nuclear myth. These archetypal cases serve as an opportunity for thinking through gaming’s fraught relationship to energy transition (a problem recently addressed by Alenda Chang, among others). They suggest that gaming’s relation to its earthly toll has never primarily been one of disavowal, but conversely that the history of video games is full of rich restagings of our entanglement in economies of extraction, marking the inseparability of culture and play from forms of dépense. The particulars of this relationship become legible through an analysis that conjugates the forms and flows internal to a game with the broader production of space (and of energy) that it plays within. Considering how these imagined “elsewheres” of extraction became central to a key late-twentieth-century art form also complicates the topologies structuring some dominant approaches to infrastructure and media, which often locate infrastructure beneath (“infra-“) or prior to media aesthetics. The centrality of the hinterlands to the history of gaming, and the persistent attraction to open planes and architectures of extraction, attests to other lineages of popular art where infrastructure was never invisible and energetic flows furnish a central problem of aesthetics.

Charli Muller, New York University: Railroad Luxemburg

Infrastructures of circulation, transportation, and communication play a central role in Luxemburg’s work in political economy as well as revolutionary strategy. This paper seeks to reconstruct and develop a theory of capitalist infrastructural expansion drawing from a variety of Luxemburg’s writings. In Accumulation of Capital, infrastructural expansion—namely of railroads—plays a central role at all stages of capitalist accumulation. Railroads act as a site of military and state investment for introducing the commodity economy to non-capitalist sectors and eventually for the “capitalist emancipation of the hinterland” (399 AOC). At the same time Luxemburg rejects the progressive character of these infrastructural endeavors, and she argues that they will not be a genuine “stamp of progress in an historical sense” until capitalism has been destroyed (Junius Pamphlet). It is no coincidence then that her political writings prominently feature figures such as railway and postal workers, who are strategically positioned to strike at the infrastructures of imperialism. A Luxemburgist theory of infrastructure has important relevance for contemporary debates around the expansion and ownership of internet infrastructures. The past decade has been marked by various calls for new models of ownership of the internet. These include The Public Service Internet Manifesto, the Democratic Socialist of America’s Internet for All Campaign, Tarnoff’s forthcoming Internet for the People, Workneh’s “Case for telecommunications commons in Ethiopia,” and netCommons Project’s vision for community networks. Such calls for a publicly owned and funded internet risk reproducing some of the dynamics Luxemburg describes in her account of the history of railroads, canals, telegraphs etc. Namely, such calls parallel the state subsidizing of an infrastructure that seeks out new sites of accumulation and extraction. This is not to say that such endeavors should be wholly abandoned, but a broader political program is necessary for the overthrow capitalism, otherwise such infrastructural expansion can be seen as continuing the expansion of capitalist accumulation. For this reason, Luxemburg’s political writings and her critique of the non-progressive nature of capitalism are also useful as she indicates how the destruction of capitalism can alter and redeem such large infrastructural projects.

3:05pm – 3:15pm – Coffee Break

3:15pm – 4:35pm – Online Elsewheres (In-person presenters; moderated by Angela Xiao Wu)

Yilun (Elon) Li, Columbia University: The Digital Journey to the West: Wall-Permeating and Chinese Internet Media Piracy as Infrastructure

This paper focuses on digital media piracy as an unauthorized yet productive form of media practice in the culture of censorship through the lens of media infrastructure, geo- blocking and cyber sovereignty, with a case study of mainland China’s Internet fansubbing and (re-)circulation of foreign audio-visual product in the 21st century. At the end of 2021, following the bust of Renren Yingshi, a company operating the PRC’s largest subtitling (translation) site and being accused of pirating more than 30,000 audio-visual products, Internet piracy once again became among the most heated topics in the country’s online community, with agitated public intellectuals and netizens assimilating the largely voluntary and less commercialized subtitle translation plus (quasi-)open source sharing behavior with the translation of Buddhist scriptures by Monk Xuanzang from India to China in the premodern era, a prominent cultural totem later adapted into the classical novel Journey to the West. That the public reaction being sympathetic with the fansubbing group (zimuzu) is indicative of the ambiguous boundary between (re-)circulation and piracy in the digital era, suggesting the analysis of piracy would be incomplete if bypassing its mediating nature as a mode of infrastructure facilitating the movement of cultural goods, as inspired by seminal works in the field of media infrastructure such as Brian Larkin’s Signal and Noise. This paper argues the digital media piracy in China could not be fully grasped without the examination of the country’s information control systems, as most typically exemplified by the Great Firewall (GFW), the Internet blocking projects initiated and launched by the government and applied to most of the network nodes in the country. Through proposing GFW as a unique type of digital infrastructure, or more precisely, a “counter-infrastructure”, a mode of negative infrastructure in service of the impossibility of communication, denial of access, and failure of connection, I examine Chinese digital piracy as a mode of “counter- counter-infrastructure” assisting cultural circulation and wall-crossing in the (semi-)grey economy in a responsive, entangled and interactive relationship with the geo-blocking system as (counter-)infrastructure. Through analysis of the mediating processes of two representative modes of counter- counter-infrastructure, namely, subtitling groups such as Renren Yingshi and digital video porters (banyungong) on user-generated-content platforms such as Bilibili, this paper challenges traditional comprehension of the encounter with VPN (Virtual Private Network) proxy as what Chinese netizens express as “wall-crossing” (fanqiang), arguing instead for a more nuanced notion of “wall-permeating,” positing the wall as a porous zone filled with contradictions and with multiple forces entangling and competing with each other, finally leading to a query into Chinese digital media piracy’s potentiality as well as limitation of functioning as a seedbed for a possible public sphere to come.

Nansong Zhou, New York University: Digital Labor in the Digital Games

A gamer’s labor includes not only their secondary game creations and their spin-offs but also their in-game participation, which includes interactions with other players, environments, and nonplayer characters (NPCs). Recently, the human-game relation has been altered because games have transformed from nonproductive activities to productive activities (Clark & Kopas, 2015; Dyer-Witheford & de Peuter, 2009; Gregg, 2011). The gamer’s secondary game creations, including writing fan fiction, modding, and drawing fan manga, are regarded as participation or labor(Kücklich, 2005), but in-game participation is ignored. The audience commodification theory also grounds to a halt in terms of social media selling users’ attention to advertisers (Hwang, 2020), and little is known about how digital games monetize players’ game playing, especially in free-to-play games. How do players in free-to-play games participate in the digital game industry? Using League of Legends as an example, this study uses political economic analysis and textual analysis together and finds that free-to-play games commodify and sell in-game player interactions, especially to players who are willing to spend money on them. Each player’s labor, therefore, comprises their interactions with other players, environments, and nonplayer characters (NPCs). This labor is exploited by LOL in three stages: labor process, remuneration settlement, and consumption. In this article, I find that videogame companies exploit players in three ways: (1) allowing players to provide more diverse interactions with other players, NPCs, and environments; (2) implementing multiple currency systems and an alternative currency system to provide labor rewards and decreasing the average remuneration that the long-term player receives for a single match; and (3) depreciating the currency a player receives for settlement remuneration and squeezing the player’s labor while enticing the player to consume using fiat currency instead of virtual currency in videogames. This study thus breaks through the notion that limits players to being consumers to help us better understand the present human- game relation and make players’ labor visible, which can improve players’ discourse power and reconstruct the power structure of the gaming industry. It enriches participatory culture theory and audience commodity theory by providing topics and perspectives on in-game interaction as labor and participation. This study also diversifies and supplies evidence for unpaid labor in digital labor studies.

Lakshita Malik, University of Illinois at Chicago: “Like and Share, Everyone!”: Privileged Instagram Creators and the Production of Hinterlands on Social Media Platforms

“I keep getting requests [from make-up artists] on Instagram for collaboration. It’s during the lockdown that everyone seems to have become an expert” [Bina, Image Consultant, November 14, 2021; New Delhi, India]. Instagram is emerging as a crucial platform for make-up artists and beauty enthusiasts to produce pleasurable visual archives of their work. Bina expresses anxiety around “everyone” taking to Instagram to perform highly valued aesthetic labor1 (Lukacs 2015), otherwise only accessible to middle-class, “upper”-caste (largely) women. Instagram, for Bina and high-end make-up artists, represents a possibility of professional advancement (courting new clients and producing brand sponsored content). This professional advancement hinges on barely visible forms of engagement creators receive from the very crowd whose unauthenticated origins bother creators like Bina. The creators who irk Bina with their “collaboration” requests are appreciated as nameless supporters who ensure visibility of her content through their “likes,” “shares,” and “following.” Even as every form of engagement becomes creative labor (Terranova 2000) appropriated by the platform, not all labor is valued equally. Collaborations require prolonged and visible, intellectual, and creative engagement; more so than just pushing buttons to “like,” “share,” and “follow.” These differently positioned practices of social engagement on platforms become sites that create hinterlands required to sustain influence and visibility on Instagram.” I explore how the platform becomes a site of (re)producing caste and class privilege through visiblizing and valuing creative labor of some over others. An understanding of direct (private) and public (to varying extent) communication enabled by Instagram and navigated by the economically and socially privileged, is important to understand how existing forms of marginalization are reoriented and reiterated. Based on ethnographic fieldwork conducted with make-up artists and beauty influencers (2019- 2022), I interrogate how the privileged reckon with existing hinterlands and produce new ones on social media.

4:35pm – 5:30pm – Break

5.30pm – 6.45pm – Keynote: Professor Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Simon Fraser University

CFP

What is peripheral and yet indispensable to media and technology production? What networks and relations may be obscured or revealed if we interrogate the constitution of the center? For the 2022 Neil Postman Graduate Conference, we focus on the centrality of the ‘elsewhere’ and the ‘otherwise’ in the production of media experiences and media technologies. To consider the many historical, geographic, economic, and material dynamics at play, we center our inquiry around the notion of the hinterlands, and invite contributions to the question: What and where are the hinterlands of media and technology?

Hinterlands are traditionally conceived as the places which supply the city, port, or metropole but which lie beyond them. Unseen, opaque, and obscure from the vantage of the center, these places are the constitutive outside without which more central worlds and more visible or overt mediations could not exist or take place. What lands, bodies, labor, and knowledge are transformed by these processes? How are groups, communities, and nations that play a central role in developing and generating media and technology excluded in their design, intended use, and distribution? How are the rural and the outskirts conceptually, politically, culturally and geographically mediated? How do new technological forms such as digital databases, algorithmic recommendation, and artificial intelligence reproduce social and spatial differences? What other forms of “elsewhere” could we consider when conceptualizing the hinterlands?

For this year’s conference, we welcome paper presentations, posters, and creative projects that engage broadly with the concept of “hinterlands” and its connection to media and technology. Early-stage projects are welcome. Topics might include, but are not limited to:

- Historical or contemporary studies of colonial and decolonial media relations

- Media and technology’s exclusion or discrimination against marginalized communities

- Rural media (practices and cultures; access and connectivity)

- The environmental impacts or local manufacturing contexts of media technology

- Accumulation, extraction, and monetization in the creative industries or in the tech industry

- Marginal, censored, or unauthorized and yet productive forms of media practice

- Phenomena beyond the traditional boundaries of media studies itself, but central to its construction